Public Health Corner: August 2025

Welcome to the Public Health Corner, a quarterly section in the Southwest Climate Outlook dedicated to exploring the intersection between climate change and public health in Arizona and New Mexico! In the Public Health Corner, we will dive into various ways in which climate influences our SW communities’ health and explore strategies to mitigate and adapt to these challenges.

This summer 2025 is another record-breaking one: June ranked as the seventh-warmest on record for the contiguous United States, averaging nearly 2.8 °F above the 20th-century average, while nighttime lows across southern Arizona and New Mexico remained as high as 87–95 °F. With this continuing intensification of extreme heat, this quarter we focus on its health impacts in Arizona and New Mexico, with a particular focus on rural and remote communities.

While only 10.7% of Arizonans and 24.7% of New Mexicans live outside metropolitan centers, rural and wilderness areas makes up more than 80% of the landmass in both states. These geographies present unique challenges for extreme heat resilience. Rural residents often contend with geographic isolation, and long travel times to healthcare or cooling infrastructure. Rural communities also have a higher prevalence of heat-sensitive conditions such as cardiovascular and respiratory disease, reflecting older populations and higher poverty rates; for example, in New Mexico, nearly 19% of the rural population is over 65, compared to 15% nationwide. Housing conditions add another layer of vulnerability, as many residents live in older homes or mobile units that are poorly insulated and less likely to have adequate cooling.

Public health data confirms the weight of these risks. While absolute numbers of heat-related emergency visits cluster in Arizona’s urban counties, the highest rates per capita occur in La Paz, Mohave, and Yuma, which are counties with large rural populations. The Arizona’s 2024 Extreme Heat Preparedness Plan acknowledged these inequities while also highlighting the difficulty of serving rural and Tribal contexts due to data gaps, logistical barriers, and limited institutional capacity. The 2025 update especially represents a step forward, emphasizing equity and institutional partnerships with rural health departments, Tribal authorities, and community organizations. New strategies include culturally tailored outreach campaigns, distribution of cooling supplies, and the deployment of mobile “Cooltainers” to expand access to air-conditioned spaces.

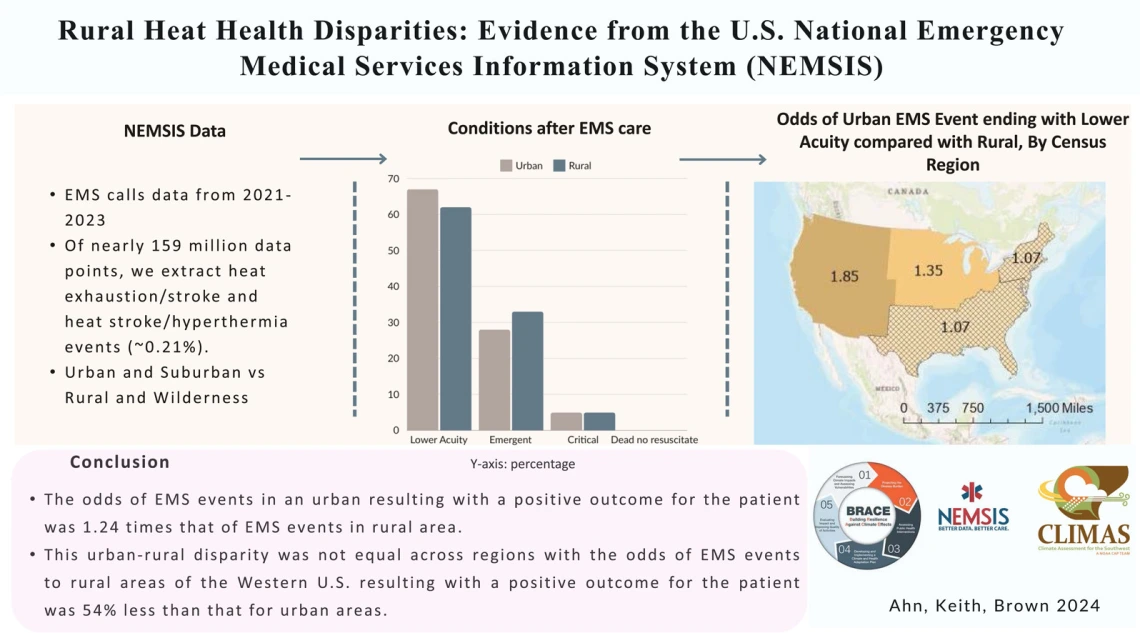

Our recent research adds further evidence for the urgency of a rural lens in extreme heat resilience planning. An analysis of the National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) (2021–2023) found that patients experiencing heat-related emergencies in rural areas had significantly worse outcomes than those in urban areas. Indeed, in the western U.S., the odds of a good outcome were 54% lower for rural patients (Ahn et al., 2025). A systematic review of 52 studies from the U.S., Canada, and Australia lead by CLIMAS Post-Docs Ahn and Boyer shows that while extreme heat is increasingly recognized as a major health threat, rural heat resilience remains overlooked. Unlike in cities, where risks are amplified by the urban heat island effect, rural risks arise from those structural vulnerabilities and governance gaps. The most affected groups include the elderly, Indigenous peoples, tourists, and especially outdoor workers such as farmworkers. This review underscores the need for integrated, place-based governance frameworks that respond to the specific conditions of rural communities (Boyer et al., forthcoming). In parallel, a national survey of heat practitioners reinforces this conclusion. While staff capacity and risk perception were identified as barriers across contexts, practitioners consistently emphasized the importance of local-scale data, tailored communication of risks, and actionable tools. Respondents working in rural settings in particular stressed that generic information is insufficient and that resilience planning must be grounded in the realities of local health systems, housing conditions, and occupational patterns (Archie et al., 2025).

Together, these studies highlight a critical gap in current heat governance: while extreme heat disproportionately affects marginalized, low-income, and in rural settings, existing frameworks still fall short in addressing their distinct vulnerabilities. Building heat resilience in the Southwest will require not only better information, but also deliberate investment in capacity-building, inclusive governance, and strategies designed for rural and remote communities that have historically been left at the periphery of public policy efforts.