Mapping the Missing Half?

An agrivoltaic system near Morogoro, Tanzania

The most important things about a place often go unmapped. England's northwest coast draws far fewer visitors than its famous southern shores. The rugged cliffs and frequent overcast skies that I’ve known since childhood fill a quiet space in local hearts while remaining largely unknown to the world beyond. When external planners decided to line this coast with wind turbines, their maps showed them sparse populations, strong winds, and relatively flat terrain for construction. Rural, affordable, seemingly empty.

What those maps couldn't capture was the daily pilgrimage of dog walkers along the coastal path, or the families sharing windswept sandwiches by the shore, or the young couples finding shelter between the rocks, watching the sun sink into the sea away from the world's watchful eyes. They missed the woman who walked the same route every evening after losing her husband, finding solace in the steady rhythm of waves against stone. The grandfather teaching his granddaughter to read tide pools was overlooked, and so too were the teenagers who gathered at the headland on summer nights, their voices carried away on salt air.

Wind turbines lining the northwest coast of England

The turbines were built regardless. Those spinning giants now mark the horizon where once there was only the whispered meeting of sky and water. I don't know if they would have been placed elsewhere if the evening walkers and tide pool explorers had been invited into the planning process. But they certainly would have felt less blindsided when their familiar landscape transformed overnight.

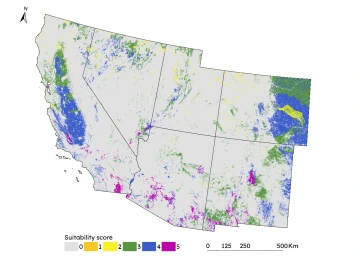

Years later, I found myself in front of my computer screen, drawing boundaries across landscapes I'd never walked, wondering if I was repeating those same mistakes. I had stumbled into a world of map making by accident during my master's degree, drawn to a project studying a relatively new field called agrivoltaics in Tanzania. The concept fascinated me, the idea that you didn't have to choose between farming and solar energy, that the two could share the same ground. My maps looked professional, authoritative. I layered data about sunlight and soil, marked distances to market, and identified terrain suitable for agrivoltaic construction. But as I stared at those neat colored polygons on my screen, I couldn't shake the feeling that something was missing. Who lived in those "suitable" areas? What did they think about the possibility of solar panels appearing above their crops? Had anyone asked them? These questions followed me from Tanzania to Arizona, growing as I spent months piecing together technical suitability maps for the American Southwest. I had become fluent in a scientific language that left me unable to hear the local dialect and felt firmly that something had to change.

A map of agrivoltaic suitability in the American southwest, where a higher score indicates higher suitability for agrivoltaics

That's what led me to this fellowship project, the sense that my maps only held half the conversation. I needed to find the other half, not to replace the technical mapping, but to expand it. Working with Extension agents and Arizona residents, I hope to explore how community voices might reshape our understanding of where agrivoltaics truly belong. Instead of adding community input as an afterthought, we're seeking to make it foundational to the mapping process itself. This approach opens possibilities for planning that honors both technical feasibility and local wisdom. The result will be a living atlas, an online platform that preserves not just the community perspectives on suitable locations, but the reasoning behind their assessments.

I don’t know what these conversations will reveal. Perhaps Arizonan farmers will point to the same areas my technical maps highlighted as optimal. Maybe they’ll identify completely different spaces, guided by knowledge about microclimates, family histories, or seasonal patterns that no coarse scale spatial dataset could detect. Most likely, the reality will be more complex than either approach alone could capture.

This atlas won’t be the final word on where agrivoltaics should go, nor is it meant to be, but it might open up a different kind of conversation about how these decisions are made. A conversation that tries to prevent the evening walkers, the tide pool explores, the farmers or land stewards, from being blindsided when their familiar landscapes transform, and instead makes them part of shaping that transformation from the start.

An agrivoltaic system near Longmont, Colorado